おすすめの製品

アッセイ

≥90% (SDS-PAGE)

品質水準

形状

liquid

比活性

≥7.0 ΔA405/h-μg protein (thiopeptide hydrolysis assay)

含まれません

preservative

メーカー/製品名

Calbiochem®

保管条件

OK to freeze

avoid repeated freeze/thaw cycles

不純物

9% TIMP-2

輸送温度

wet ice

保管温度

−70°C

詳細

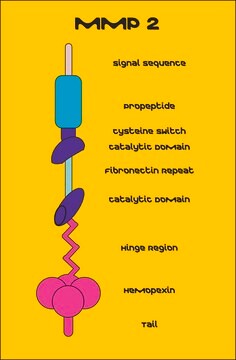

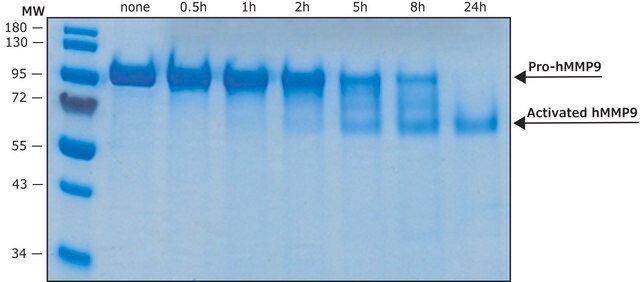

Full-length, recombinant, human pro-MMP-2 expressed in mouse cells that is subsequently activated by APMA. APMA is removed through a desalting column. The substrate specificity for MMP-2 includes collagen (types IV, V, VII, and X), elastin, and gelatin (type I). The presence of TIMP-2 inhibitor prevents degradation of the MMP-2 C-terminal regulatory domain. TIMP-2 is also an inhibitor of proteolysis and will inhibit the activity of the enzyme. Useful for immunoblotting, substrate cleavage assay and zymography.

Full-length, recombinant, human pro-MMP-2 expressed in mouse cells that is subsequently activated by APMA. APMA is removed through a desalting column. The substrate specificity for MMP-2 includes collagen (types IV, V, VII, and X), elastin, and gelatin (type I). The presence of TIMP-2 inhibitor prevents degradation of the MMP-2 C-terminal regulatory domain. TIMP-2 is also an inhibitor of proteolysis and will inhibit the activity of the enzyme. Useful for immunoblotting, substrate cleavage assay and zymography.

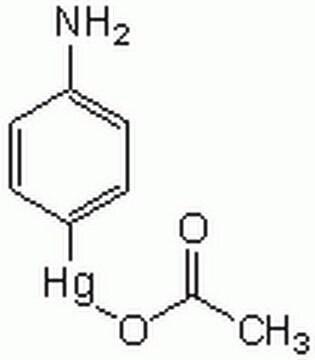

Matrix metalloproteinases are members of a unique family of proteolytic enzymes that have a zinc ion at their active sites and can degrade collagens, elastin and other components of the extracellular matrix (ECM). These enzymes are present in normal healthy individuals and have been shown to have an important role in processes such as wound healing, pregnancy, and bone resorption. However, overexpression and activation of MMPs have been linked with a range of pathological processes and disease states involved in the breakdown and remodeling of the ECM. Such diseases include tumor invasion and metastasis, rheumatoid arthritis, periodontal disease, and vascular processes such as angiogenesis, intimal hyperplasia, atherosclerosis, and aneurysms. Recently, MMPs have been linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer′s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Natural inhibitors of MMPs, tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs) exist and synthetic inhibitors have been developed which offer hope of new treatment options for these diseases. Regulation of MMP activity can occur at the level of gene expression, including transcription and translation, level of activation, or at the level of inhibition by TIMPs. Thus, perturbations at any of these points can theoretically lead to alterations in ECM turnover. Expression is under tight control by pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and/or growth factors and, once produced the enzymes are usually secreted as inactive zymograms. Upon activation (removal of the inhibitory propeptide region of the molecules) MMPs are subject to control by locally produced TIMPs. All MMPs can be activated in vitro with organomercurial compounds (e.g., 4-aminophenylmercuric acetate), but the agents responsible for the physiological activation of all MMPs have not been clearly defined. Numerous studies indicate that members of the MMP family have the ability to activate one another. The activation of the MMPs in vivo is likely to be a critical step in terms of their biological behavior, because it is this activation that will tip the balance in favor of ECM degradation. The hallmark of diseases involving MMPs appear to be stoichiometric imbalance between active MMPs and TIMPs, leading to excessive tissue disruption and often degradation. Determination of the mechanisms that control this imbalance may open up some important therapeutic options of specific enzyme inhibitors.

Matrix metalloproteinases are members of a unique family of proteolytic enzymes that have a zinc ion at their active sites and can degrade collagens, elastin and other components of the extracellular matrix (ECM). These enzymes are present in normal healthy individuals and have been shown to have an important role in processes such as wound healing, pregnancy, and bone resorption. However, overexpression and activation of MMPs have been linked with a range of pathological processes and disease states involved in the breakdown and remodeling of the ECM. Such diseases include tumor invasion and metastasis, rheumatoid arthritis, periodontal disease, and vascular processes such as angiogenesis, intimal hyperplasia, atherosclerosis, and aneurysms. Recently, MMPs have been linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer′s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Natural inhibitors of MMPs, tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs) exist and synthetic inhibitors have been developed which offer hope of new treatment options for these diseases. Regulation of MMP activity can occur at the level of gene expression, including transcription and translation, level of activation, or at the level of inhibition by TIMPs. Thus, perturbations at any of these points can theoretically lead to alterations in ECM turnover. Expression is under tight control by pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and/or growth factors and, once produced the enzymes are usually secreted as inactive zymograms. Upon activation (removal of the inhibitory propeptide region of the molecules) MMPs are subject to control by locally produced TIMPs. All MMPs can be activated in vitro with organomercurial compounds (e.g., 4-aminophenylmercuric acetate), but the agents responsible for the physiological activation of all MMPs have not been clearly defined. Numerous studies indicate that members of the MMP family have the ability to activate one another. The activation of the MMPs in vivo is likely to be a critical step in terms of their biological behavior, because it is this activation that will tip the balance in favor of ECM degradation. The hallmark of diseases involving MMPs appear to be stoichiometric imbalance between active MMPs and TIMPs, leading to excessive tissue disruption and often degradation. Determination of the mechanisms that control this imbalance may open up some important therapeutic options of specific enzyme inhibitors.

包装

Please refer to vial label for lot-specific concentration.

警告

Toxicity: Standard Handling (A)

その他情報

Liepnisch, E., et al. 2003. J. Biol. Chem.278, 25982.

Parsons, S.L., et al. 1997. Br. J. Surg.84, 160.

Backstrom, J.R., et al. 1996. J. Neuro.16, 7910.

Lim, G.P., et al. 1996. J. Neurochem.67, 251.

Xia, T., et al. 1996. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1293, 259.

Chandler, S., et al. 1995 Neuroscience Letters201, 226.

Sang, Q.X., et al. 1995. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1251, 99.

Kenagy, R.D. and Clowes, A.W. 1994. In Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteinases: Therapeutic Potential. Greenwald, R.A. and Golub L.M., Eds, 465.

Zempo, N., et al. 1994. J. Vasc. Surg.20, 217.

Birkedal-Hansen, H. 1993. J. Periodontol.64, 484.

Stetler-Stevenson, W.G., et al. 1993. FASEB J.7, 1434.

Delaisse, J-M. and Vaes, G. 1992. In Biology and Physiology of the Osteoclast. B.R. Rifkin and C.V. Gay, Eds., 290.

Jeffrey, J.J. 1992. In Wound Healing: Biochemical and Clinical Aspects. R.F. Diegelmann and W.J. Lindblad, Eds., 194.

Jeffrey, J.J. 1991. Semin. Perinatol.15, 118.

Liotta, L.A., et al. 1991. Cell64, 327.

Harris, E. 1990. N. Engl. J. Med.322, 1277.

Parsons, S.L., et al. 1997. Br. J. Surg.84, 160.

Backstrom, J.R., et al. 1996. J. Neuro.16, 7910.

Lim, G.P., et al. 1996. J. Neurochem.67, 251.

Xia, T., et al. 1996. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1293, 259.

Chandler, S., et al. 1995 Neuroscience Letters201, 226.

Sang, Q.X., et al. 1995. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1251, 99.

Kenagy, R.D. and Clowes, A.W. 1994. In Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteinases: Therapeutic Potential. Greenwald, R.A. and Golub L.M., Eds, 465.

Zempo, N., et al. 1994. J. Vasc. Surg.20, 217.

Birkedal-Hansen, H. 1993. J. Periodontol.64, 484.

Stetler-Stevenson, W.G., et al. 1993. FASEB J.7, 1434.

Delaisse, J-M. and Vaes, G. 1992. In Biology and Physiology of the Osteoclast. B.R. Rifkin and C.V. Gay, Eds., 290.

Jeffrey, J.J. 1992. In Wound Healing: Biochemical and Clinical Aspects. R.F. Diegelmann and W.J. Lindblad, Eds., 194.

Jeffrey, J.J. 1991. Semin. Perinatol.15, 118.

Liotta, L.A., et al. 1991. Cell64, 327.

Harris, E. 1990. N. Engl. J. Med.322, 1277.

法的情報

CALBIOCHEM is a registered trademark of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany

シグナルワード

Danger

危険有害性情報

危険有害性の分類

Resp. Sens. 1A

保管分類コード

10 - Combustible liquids

WGK

WGK 1

引火点(°F)

No data available

引火点(℃)

No data available

適用法令

試験研究用途を考慮した関連法令を主に挙げております。化学物質以外については、一部の情報のみ提供しています。 製品を安全かつ合法的に使用することは、使用者の義務です。最新情報により修正される場合があります。WEBの反映には時間を要することがあるため、適宜SDSをご参照ください。

Jan Code

PF023-5UG:

試験成績書(COA)

製品のロット番号・バッチ番号を入力して、試験成績書(COA) を検索できます。ロット番号・バッチ番号は、製品ラベルに「Lot」または「Batch」に続いて記載されています。

この製品を見ている人はこちらもチェック

Sunyoung Jeong et al.

International wound journal, 14(5), 786-790 (2016-12-10)

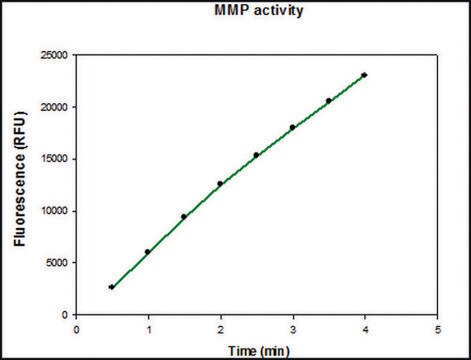

Proteinases are enzymes that can digest other proteins. In chronic wounds, a sub-class of these enzymes with the ability to degrade the extracellular matrix (matrix metalloproteinases, MMPs) have been found to both inhibit healing and to be able to aid

ライフサイエンス、有機合成、材料科学、クロマトグラフィー、分析など、あらゆる分野の研究に経験のあるメンバーがおります。.

製品に関するお問い合わせはこちら(テクニカルサービス)